AI affords the opportunity to transform planning, problem solving and public services.

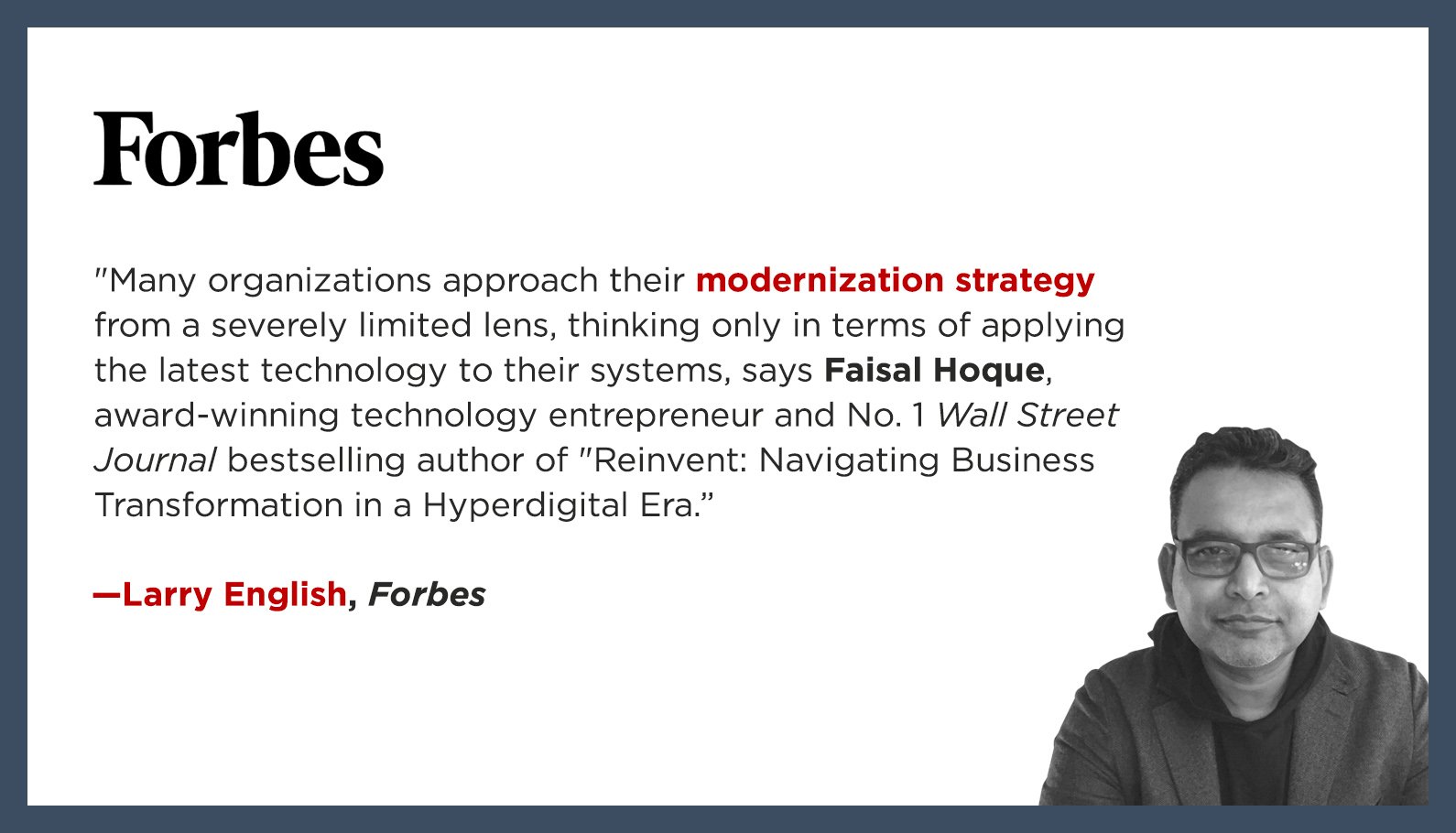

[This article is adapted from the #1 Wall Street Journal and USA Today best selling book LIFT by Faisal Hoque.]

Much has been made about the varied opportunities the Fourth Industrial Revolution (4IR) affords companies and organizations of all sorts. That’s a perfectly justifiable discussion.

But what’s often overlooked are the possibilities in the public sector—government entities, citizens and others who might assume that 4IR’s impact somehow or another misses them.

As I examined in my bestselling book LIFT, government now serves a citizen population that is far more informed and involved in the areas of governance and public services in a positive and productive manner. And, like everything from health care to education, these empowered citizens can best be treated as consumers—end users who have every right to expect a high return from what they invest in taxes and other forms of financial support for government.

As I examined in my bestselling book LIFT, government now serves a citizen population that is far more informed and involved in the areas of governance and public services in a positive and productive manner. And, like everything from health care to education, these empowered citizens can best be treated as consumers—end users who have every right to expect a high return from what they invest in taxes and other forms of financial support for government.

That’s a healthy dynamic in many ways. On the one hand, increasing pressure from citizenry on government to perform better, faster and more efficiently will likely prove a powerful catalyst for productive change. And, like a customer at a particular store who returns to shop again and again following a great experience, a government which offers high quality, responsive service can not only satisfy citizens that their money is being well spent, but it can also induce them to greater levels of involvement and support—particularly financially, if or when that becomes necessary.

Artificial intelligence is a hallmark of this evolving digital government. AI affords the opportunity to transform planning, problem solving and public services. For instance, the city of Pittsburgh has adopted AI-enabled traffic lighting, which has cut travel times by 25 percent and idling times by 40 percent, reducing pollution levels. Other areas where artificial intelligence can prove advantageous include optimization of public transportation, oversight of public garbage and recycling programs and general public safety, such as nighttime pedestrian traffic.

Another boon of AI is its capacity to liberate government employees—theoretically at least, even at the most local level—from rudimentary and often mundane responsibilities. For instance, human employees inevitably take a great deal of time to manually process large amounts of data, particularly the massive information collected by the military, aerospace and other government sectors. But AI completes time-consuming—and tedious—tasks quickly and accurately. As a result, government workers have more time to devote their energy to other responsibilities.

For example, the United States Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) uses a computer-generated virtual assistant named Emma to answer questions and direct individuals to the right area of the bureau’s website.

Should further information and clarification prove necessary, a government employee can step in to help out.

AI can also play a significant role in military matters. These include improving situational awareness and decision-making; increasing the safety of equipment like aircraft, ships, and vehicles in dangerous situations; and predicting when critical parts will fail, automating diagnosis and scheduling routine maintenance. AI also helps improve the nautical, terrain, and aeronautical charting vital to Department of Defense missions, helping enable safe and precise navigation and more comprehensive surveillance. That’s a boon to national security.

Policymaking is still another area ripe with promise. As is the case with so much to do with government, policy makers are often overwhelmed by information that needs to be checked and placed into context before even beginning the development of actual policy. Further complicating this challenge is the presence of lobbyists—deep pocketed people and groups with specific priorities far too often out of line with the public’s best interests.

Not only will AI and related technology allow policymakers to better manage and analyze growing amounts of valuable data, but technology also affords new venues in which proposed policies and other governmental actions can be simulated and carried out—so-called regulatory “sand boxes.” Not only does that permit detailed study of the impact and ramifications of such potential decisions, but harmless “dry runs” let government fully dissect policy, legislation and other steps before they actually go into effect.

A willingness to embrace and implement technology also affords government at all levels the opportunity to be that much more competitive when fostering economic growth and development. For example, in Estonia, the “e-Estonia11” initiative serves as a government-operated incubator for breakthrough ideas concerning digital citizenship, security, virtual business and education. On a more local level, the city of Boston has partnered with the World Economic Forum to investigate the use of autonomous vehicles to reduce accidents throughout the city. The program also serves to showcase Boston as a forward thinking metropolitan area interested in and receptive to all sorts of technological possibilities—not a bad bit of public relations.

Greater overall collaboration is also made possible. While it’s a central necessity for government to take full advantage of the opportunities afforded by technology and other drivers of change, that doesn’t have to happen on its own. In so many words, evolving models of government should acknowledge that effective governance in the future will mandate partnerships with the private sector and other non-governmental stakeholders.

It makes sense on any number of levels. For one thing, as is the case with individuals, evolving technology has shifted autonomous influence away from government toward a more cooperative, collaborative environment. Moreover, it’s in government’s own best interests to partner with and follow the lead of private entities. Given government’s history of deliberate adoption of new tools and procedures, far better to work closely with others who are far more proactive and responsive to such change. That may go a long way toward preventing the amount of change outpacing government’s ability to remain as current as possible, not to mentioning offering partners from whom government can learn through both example and hands on, experiential activity.

Lastly, nurturing partnerships between government entities and others reinforces the argument that “going it alone” is becoming implausible in a fast changing world. To meet increasingly complex and challenging issues, government should leverage the knowledge and resources of the private sector to foster better governmental and policy outcomes. That’s a level of collaboration where everyone involved benefits rather than a select few—the best possible outcome in a changing, evolving society.

© 2022 by Faisal Hoque. All rights reserved.